by Morgan Campbell

The 2018 World Health Organization (WHO) report on Road Safety identified India as having one the highest number of road-related deaths in the world; approximately 23 deaths per 100,000 people per year.

Several factors contribute to dangerous conditions for drivers, passengers, and pedestrians. Roads requiring repair, lack of coordinated traffic laws and enforcement, drunk driving, rash driving, and monsoon rains are examples of elements that affect road safety. The ubiquity of potholes alone kills an average of seven people per day in the country. Some see the prevalence of transport-related injuries and deaths as a failure of the government.

Within the past two years, several states (e.g. Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka) have laid groundwork for the establishment of a road safety fund. The purpose of such a fund is to address issues and fund initiatives that can improve the safety of all users of streets and highways. This is a difficult undertaking as state budgets are already overwhelmed.

During a recent project visit to Kochi, I had the unexpected pleasure of meeting Mr Najeeb, a man helping to expand Kerala’s Road Safety Authority (KRSA), a body which has been in place since 2012. To my knowledge this is the longest-running Road Safety Authority in the country.

Mr Najeeb gave an overview of the Authority; why Kerala thought road safety should be a priority and some of the ongoing projects. He articulated the work of the Authority through the example of the Safe Sabarimala Zone, a successful campaign that began in 2013 (as reported by national news outlets The Hindu and New Indian Express). Sabarimala is a temple high in the mountains within the Periyar Tiger Reserve. During pilgrimage season, many worshippers travel through the night in order to see the temple at sunrise. Poor road conditions and speeding motorists have led to recurring accidents within a 13-kilometre area.

The road safety committee started a campaign that saw two police officers and an ambulance patrolling the area 24 hours a day. Mr Najeeb described how police officers would keep thermos flasks of fresh coffee at hand each evening, stopping speeding drivers and encouraging them to take a break, have a fresh coffee, and drive more slowly as they continued on.

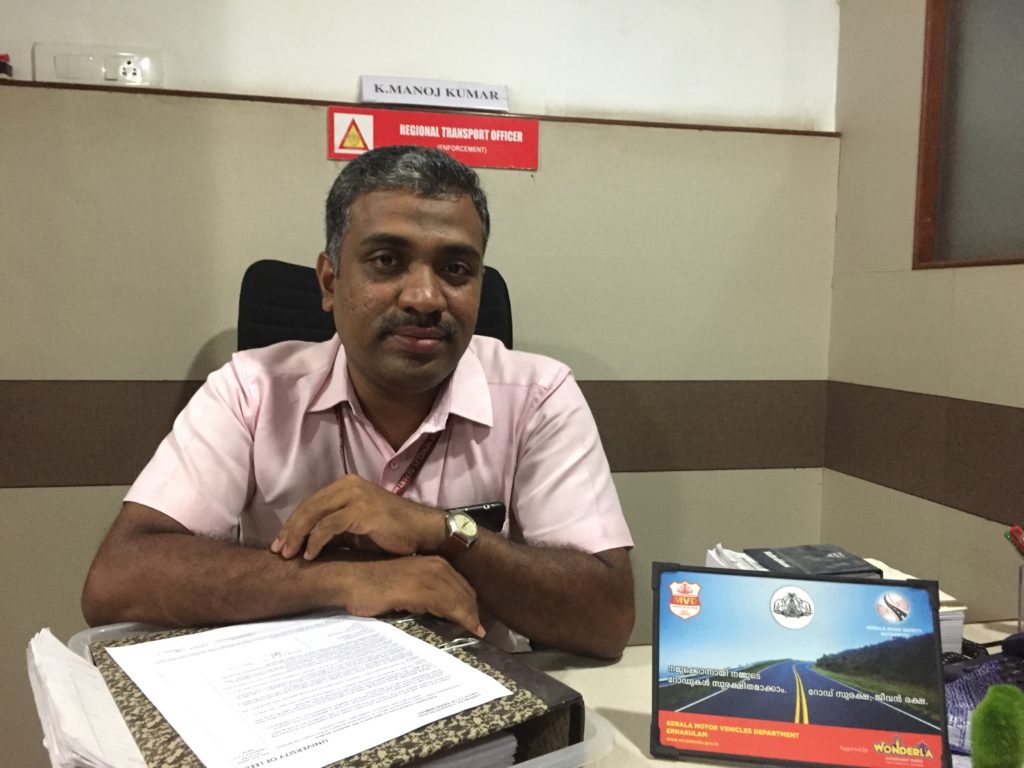

KRSA operates through the Motor Vehicles Department (MVD) of the Regional Transport Office (RTO; a state-level agency). The MVD itself is a district-level agency, through which the automated enforcement unit was created. Mr Najeeb explained that the need for an automated enforcement unit came out of a lack of enforcement capacity. In Kerala, there is approximately one traffic officer for every 20,000 vehicles.

The idea for using automation as a form of road safety monitoring came about in 2012, when Kerala’s Centre for Development of Advanced Computing designed speciality CCTV cameras to be used along the state and national highways, the roads where most vehicle-related injuries and deaths occur. These cameras were larger, more robust versions of the standard CCTV camera. Because the cameras were manufactured in-state, it was an affordable project to implement. The Centre for Computing worked with the Centre for Development of Imaging Technology to create an automated, real-time recording system for traffic violations and road accidents.

The RTO and MVD then established a small command and control centre for 24-hour monitoring of the specific sites where the cameras were installed. Even with the help of automation, there is not enough human power to monitor the frequency of violations or issue violation tickets, meaning many offences go unchallenged.

Nevertheless, revenue obtained from fines goes into the state’s road safety fund. The fund is managed by a road safety council and every district in the state has its own council to deal with issues unique to their area.

When asked about future directions for the fund, Mr Najeeb stated that more investment was needed for both the integration and coordination of different agencies, as well as the integration of infrastructure. He pointed out that a police officer cannot fine someone for jumping a traffic signal if there is no line demarcating where the car needs to stop. A demarcation, however, cannot be made if the roads are not in good condition.

Mr Najeeb believes that the ultimate goal for the safety fund is to ensure that all people are able to “come out for transportation.” One way to do this is to make sure the streets are “smooth and safer” for everyone and this can be achieved “when all the departments…come together.”

Safer streets and better departmental coordination may become possible with planned expansions for Kochi’s new command and control centre. Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCC) have become a spotlight project in many of the larger cities taking part in India’s Smart City Mission .

For the most part, ICCCs are conceived of as a powerhouse of data collection and analysis. Their main purpose is to regulate and monitor all urban infrastructures and services; this includes increased use of e-governance on the part of citizens.

Toted as the ‘brain of the city,’ for which smart sensors and CCTV cameras will become the ‘eyes and ears,’ the Integrated Command and Control Centre can at times feel a bit dystopian in its descriptive monitoring of citizens ‘every move’. However, when seen through the lens of Kerala’s automated enforcement unit and the KRSA, a different picture emerges.

In Kochi, the Integrated Command and Control Centre will be housed within the existing RTO department, which is also home to the automated enforcement unit. The current control centre will expand and it is anticipated that the KRSA will benefit from having more access to more CCTV cameras on urban roads.

One drawback to the current monitoring system is that cameras are only installed on National and State Highways. The future Integrated Command and Control Centre is focused on Kochi city, which will allow for more coverage of monitoring. This will be further facilitated through the employment of more officers for human-based monitoring and issuing of tickets.